Meiyan LI

Chinese Attorney-at-Law

Chinese Attorney-at-Law

One day in the second half of 2021, the author attended the second-instance trial of an administration litigation for a refusal appeal as the attorney of the applicant of the disputed mark, and was informed by the litigation representative of the appellee, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (“CNIPA”), that at present, the CNIPA basically does not accept the Letter of Consent / Coexistence Agreement. After the trial, the author immediately reviewed the results whether the CNIPA accepted the Letters of Consent / Coexistence Agreements in the administrative stage of refusal appeal. The search has revealed that from the cases our firm represented and combined with the statistics from Mozlen Database, the CNIPA had basically rejected the Letter of Consent / Coexistence Agreement since September 2021, mainly due to the reason that the waiver or transfer of its own right by the owner of cited trademark would not necessarily exclude the likelihood of confusion amongst the consumers.

Then here comes the question whether the courts share a similar opinion with the CNIPA and hold a basically negative attitude towards Letter of Consent / Coexistence Agreement.

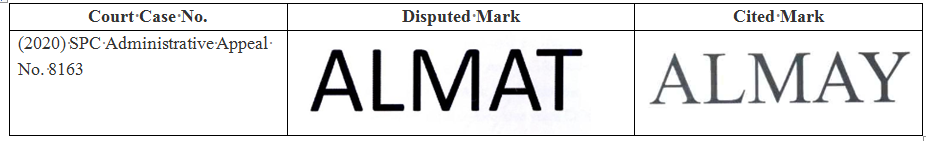

As for the application of Letter of Consent / Coexistence Agreement, there is no clear provision in the law, and trademark right, as a civil property right, according to the principle of autonomy of will, can be disposed by its right owner according to their own will, unless it involves major public interests. Combined with the actual situation of trademark adjudication, Beijing Higher People’s Court has stipulated the legal effects of Coexistence Agreement in Article 15.12 of the Guidelines for the Trial of Administrative Cases of Trademark Right Granting and Verification. Pursuant to the Guidelines, the Coexistence Agreement is only prima facie evidence to exclude the likelihood of confusion caused amongst the relevant public by the two trademarks, and if there is no other evidence to prove that the coexistence of the disputed trademark and the cited trademark will cause confusion amongst the relevant public with respect to the source of goods, the court may determine that the two trademarks do not constitute similar trademarks. However, when the court holds that the degree of similarity of the two trademarks is high and could easily mislead or cause confusion amongst the relevant public with respect to the source of goods, even if a Coexistence Agreement has been issued, the obstacle to registration could not be removed. In the case (2020) SPC Administrative Appeal No. 8163, the Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) also pointed out that for trademarks designated for use with respect to similar goods that are highly similar, the Coexistence Agreement will not necessarily exclude the possible market confusion amongst the relevant public.

Then here comes the question whether the courts share a similar opinion with the CNIPA and hold a basically negative attitude towards Letter of Consent / Coexistence Agreement.

As for the application of Letter of Consent / Coexistence Agreement, there is no clear provision in the law, and trademark right, as a civil property right, according to the principle of autonomy of will, can be disposed by its right owner according to their own will, unless it involves major public interests. Combined with the actual situation of trademark adjudication, Beijing Higher People’s Court has stipulated the legal effects of Coexistence Agreement in Article 15.12 of the Guidelines for the Trial of Administrative Cases of Trademark Right Granting and Verification. Pursuant to the Guidelines, the Coexistence Agreement is only prima facie evidence to exclude the likelihood of confusion caused amongst the relevant public by the two trademarks, and if there is no other evidence to prove that the coexistence of the disputed trademark and the cited trademark will cause confusion amongst the relevant public with respect to the source of goods, the court may determine that the two trademarks do not constitute similar trademarks. However, when the court holds that the degree of similarity of the two trademarks is high and could easily mislead or cause confusion amongst the relevant public with respect to the source of goods, even if a Coexistence Agreement has been issued, the obstacle to registration could not be removed. In the case (2020) SPC Administrative Appeal No. 8163, the Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) also pointed out that for trademarks designated for use with respect to similar goods that are highly similar, the Coexistence Agreement will not necessarily exclude the possible market confusion amongst the relevant public.

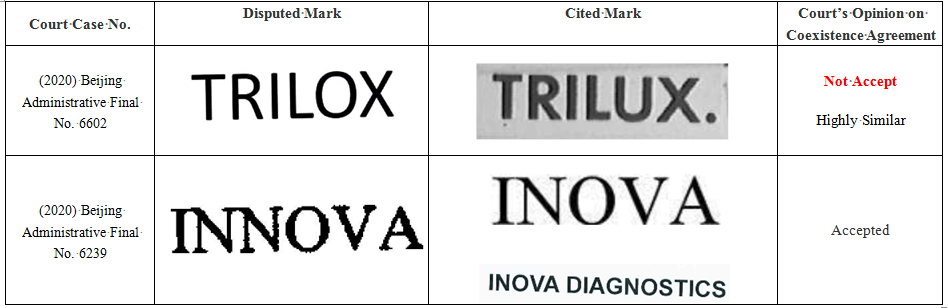

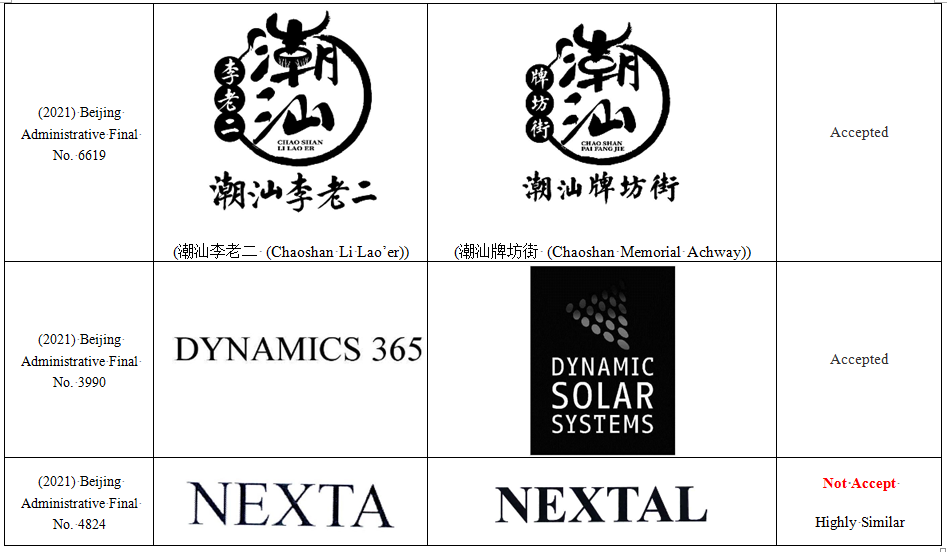

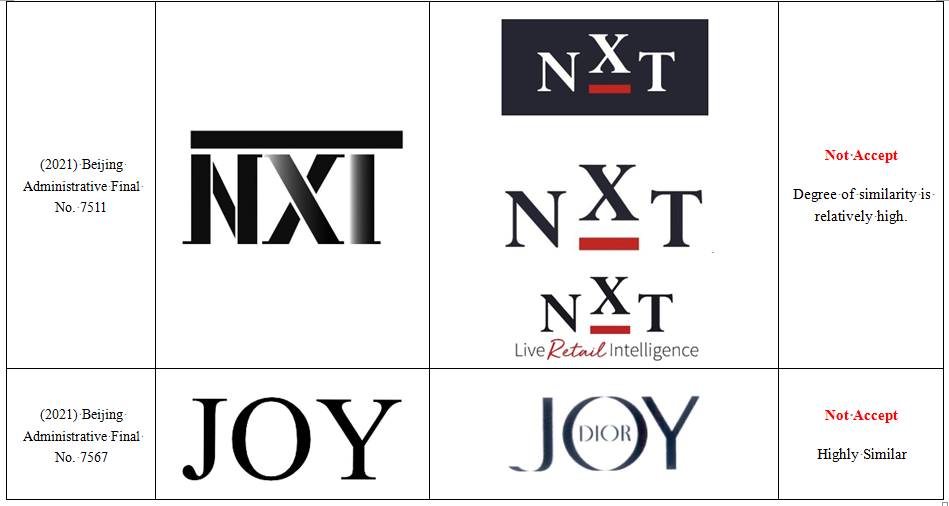

The author has searched on the database of Wolters Kluwer for administrative litigation cases on trademark refusal appeals involving Coexistence Agreements from September 2021 to the present, i.e. May 2022, and has revealed the following twelve (12) cases[i] where the court has made relevant determinations from the perspective of whether the Coexistence Agreement can exclude the likelihood of confusion. Further, in five (5) of these cases, the court did not accept the Coexistence Agreement on the grounds that the disputed trademark and the cited mark were highly similar or substantially identical, while in seven (7) cases the court found that there was a certain difference between the disputed mark and the cited mark and the coexistence thereof would not cause confusion amongst the relevant public.

It can be seen from the above-listed trademarks that in the cases where the Coexistence Agreement was not accepted, the disputed trademark and the cited trademark are merely different in one word or letter or basically the same. If both marks are used with respect to the same or similar goods, it may not exclude the likelihood of confusion amongst the relevant public. If the disputed trademark is registered, it will harm the interests of consumers. On the other hand, in the cases where the Coexistence Agreement was accepted, the court held that if the right owner of the cited trademark has issued a Coexistence Agreement, in the absence of other evidence to prove that the coexistence of the disputed trademark and the cited mark will cause a likelihood of confusion amongst the relevant public with regards to the source of goods, it could be found that the disputed trademark and the cited trademark did not constitute similar trademarks. In the cases where Coexistence Agreements have been accepted, there are also cases where the disputed trademark and the cited trademark only differ in one word or letter, which indicates that the court’s determination standard has not been tightened so far.

Based on the above, the risk that the Coexistence Agreement will not be accepted at the stage of the CNIPA has increased significantly, and if the applicant wishes to pursue a final victory, then the action should be persisted to the litigation stage. According to the current criteria for determination, in the circumstance where the disputed trademark and the cited trademark are not identical or highly similar, there is still a great possibility of removing the obstacle to registration by a Coexistence Agreement. In the meanwhile, the Coexistence Agreement shall be true, legal and valid, and there shall be no circumstances that harm the interests of the state, the public interest, or the lawful rights and interests of third parties. In practice, there are many cases where the authenticity of the Coexistence Agreement has not been accepted due to the reason that it was not notarized or legalized, or cannot prove whether the person signing the Coexistence Agreement has the authority to sign on behalf of the company. Therefore, when issuing a Coexistence Agreement, special attention should be paid to whether the procedural requirements are met.

Finally, in the litigation case mentioned by the author at the beginning of this article, the second-instance judgment made by the court in January 2022 made the following decision that, “in trademark application procedure, the determination of the likelihood of confusion in Article 31 of the Trademark Law is a judgment made by the trademark administrative authority or the court from the perspective of the relevant public, while the Letter of Consent is a restriction on the prior right of the cited trademark, which is more in line with the actual market and business situation. Therefore, in the case that the disputed trademark and the cited trademark have certain differences, a Letter of Consent is usually a piece of convincing evidence to exclude the likelihood of confusion, which can be used as a factor to be considered when applying Article 31 of the Trademark Law to examine whether the disputed trademark can be approved for registration.”

As such, and as you can see, Letter of Consent still works!

[i] Only effective judgments can be made public, and they are not publicly available immediately after they take effect. In addition, most of the above twelve (12) judgments were made in December 2021.