Yan WANG

Chinese Trademark Attorney

Chinese Attorney-at-Law

Wei Chixue Law Firm

Chinese Trademark Attorney

Chinese Attorney-at-Law

Wei Chixue Law Firm

Introduction

Trademark use is a core concept within the trademark legal system, directly impacting the acquisition and maintenance of trademark rights, as well as the determination of infringement. It holds significant importance in corporate brand strategy. Recent amendments to trademark law have shown an increasing emphasis on trademark use. For instance, the amended Trademark Law of 2019 explicitly requires that trademark applications be based on the need for use, and bad faith applications filed without the intent to use shall not be approved for registration. Furthermore, Trademark Law (Amendment Draft) for Public Comment further strengthens the obligation to use trademarks by introducing systems such as the “obligation to commit to trademark use” and “explanation of trademark use.” Thus, the importance of trademark use in trademark legal practice has become increasingly prominent. This article aims to explore the specific role of trademark use in trademark authorization, determination, and infringement defense, based on current legal provisions and relevant cases, in order to provide reference for trademark legal practice.

I. What Constitutes Trademark Use

Before discussing the role of trademark use, it is essential to clarify its definition. Article 48 of the Trademark Law defines “trademark use” as “the act of using a trademark on goods, their packaging or containers, or in transaction documents related to goods, or using a trademark in advertising, promotion, exhibitions, or other business activities, to identify the source of the goods.”

This definition highlights that the core function of a trademark is to distinguish the providers of goods or services. If an act of using a trademark fails to establish a connection between the mark and the provider of the goods or services, it does not constitute trademark use in the legal sense. Furthermore, trademark use must be based on a genuine and good-faith business purpose, rather than being a token use merely to maintain trademark rights. The use should also be consistent and stable.

In terms of forms of use, a trademark can be directly affixed to the goods themselves, their packaging, or containers. It can also be embodied in transaction documents such as contracts and invoices, or employed in marketing and promotional contexts like advertising, media campaigns, and exhibitions.

Special emphasis must be placed on acts of trademark use relating to the services in Class 35, which covers services closely related to business operations, such as advertising, marketing, and business management. However, this does not mean that merely using a trademark in activities like advertising or promotions automatically constitutes trademark use in Class 35—a point often misunderstood by many trademark applicants.

In fact, when an enterprise uses its trademark while selling its own goods, advertising to promote its own goods, or engaging in routine business management and analysis for its own operational needs, such acts do not constitute trademark use in Class 35. The distinctive feature of Class 35 services lies in providing such services for others, rather than performing the activities for one's own needs. For example, when a company promotes its own goods and uses the trademark of those goods in advertising, the trademark establishes a connection with the “supplier of the goods”, not with an “advertising service provider”. Therefore, such use does not constitute trademark use in advertising services.

II. The Role of Trademark Use in Trademark Authorization and Determination

During the trademark authorization and determination stages, use serves as a critical foundation for acquiring exclusive trademark rights. For signs lacking inherent distinctiveness, use can enable them to have “acquired” distinctiveness, thereby making them eligible for registration. For already registered trademarks, consistent use can enhance their recognition, thereby earning themselves a broader scope of protection. As for unregistered trademarks, if they have been put into use, they may also qualify for protection under the Trademark Law under specific conditions. It is evident that trademark use plays a vital role within the trademark authorization and determination system. Below, I will elaborate on the role of trademark use in trademark authorization and determination cases by referencing Articles 11, 13, 15, and 32 of the Trademark Law.

1. From “Unregistrable” to “Registrable”

Article 11(1) of the Trademark Law explicitly stipulates that signs lacking distinctiveness cannot be registered as trademarks. Distinctiveness is a prerequisite for trademark registration. Many signs inherent lack the inherent distinctiveness required of a trademark, making it difficult for them to function in distinguishing different producers or operators. However, the distinctiveness of a trademark is a rather intriguing attribute—it is not immutable. Some signs that originally lack trademark distinctiveness are not permanently barred from registration; likewise, a registered trademark may not always maintain its distinctiveness. The actual use of a trademark is a primary factor that can alter its distinctiveness.

According to Article 11(2) of the Trademark Law, where the signs listed in the preceding paragraph have acquired distinctiveness through use and are easy to identify, they may be registered as trademarks. This demonstrates that the distinctiveness of a trademark can be acquired subsequently through use.

In trademark practice, if a trademark application is rejected due to a lack of distinctiveness, the applicant can initiate a review procedure and submit substantial evidence of use to demonstrate that the mark has acquired distinctiveness through use, thereby overcoming the ground for rejection. Based on practical experience, the requirements for evidence of use in such cases are exceptionally high. In the author's opinion, the standard of proof can generally be compared to that for well-known trademarks.

In the Tencent case regarding the review of the rejection of the “Dī Dī Dī Dī Dī Dī” (sound mark) trademarki, Tencent submitted extensive evidential materials. These included the company’s annual reports over the years, literature searches from the National Library, relevant industry reports such as the “China Instant Messaging Research Report” issued by professional consulting firms, records of the QQ trademark being recognized as a well-known trademark on multiple cases, and the certificates and related reports about the QQ software receiving the Guinness World Record for the “Most People Online Simultaneously on a Single Instant Messaging Platform.” This evidence was used to prove that the QQ software had an extremely broad user base and enjoyed high recognition among the relevant public. The sound mark in question was the default notification sound for new messages in the QQ software, meaning that using the QQ software necessarily involved exposure to this sound. The popularity of the QQ software, to a certain extent, directly reflected the recognition of this notification sound.

The court held that although the sound mark consisted merely of a single, repeating “Dī” sound, which the relevant public would not normally perceive as a sign identifying the source of goods or services, thus falling under the signs lacking distinctiveness stipulated in Article 11(1)(3) of the Trademark Law, the prolonged and continuous use by Tencent had enabled this sound mark to acquire a distinctive feature of identifying the source of services. According to Article 11(2) of the Trademark Law, it should therefore be approved for registration.

In this case, the court further clarified that the examination of trademarks that have acquired distinctiveness through use must adhere to the principle of “specialization of goods and service items.” This is to avoid overextended application or overgeneralized handling in the course of the determination of acquired distinctiveness. Tencent’s “Dī Dī Dī Dī Dī Dī” sound mark acquired distinctiveness through long-term use on its instant messaging software. Among the services for which the mark was designated, “message sending; providing online forums; computer aided transmission of messages and images; providing internet chat rooms; transmission of digital files; transmission of greeting cards online; transmission of electronic mail” are closely related to instant messaging software and fall within the services provided by that software platform. Therefore, for these designated services, the sound mark could be recognized as having acquired distinctiveness.

However, the sound mark had not been used on the three other designated services: “television broadcasting; news agency services; teleconferencing services.” If it is deemed to have acquired distinctiveness in respect of these three services, this would be inconsistent with the factual finding that trademark distinctiveness is acquired through use, and improperly reserve registration space for the applied-for mark.

Accordingly, where the acquisition of a trademark’s distinctiveness is based on use, the scope of goods or services for which registration is granted should be limited to those on which the mark has been actually used. When a mark has acquired distinctiveness through extensive use on one product, such distinctiveness does not automatically extend to other products.

2. Cornerstone of “Cross-Class Protection”

Pursuant to Article 13(3) of the Trademark Law of China, well-known trademarks that are registered in China are entitled to cross-class protection on non-similar goods. Typically, trademark protection is confined to the scope of similar goods or services for which the trademark is approved for registration. However, once a trademark is recognized as well-known, its scope of protection is significantly expanded, and the strength of such protection is substantially enhanced.

The actual use of a trademark is a necessary prerequisite for it to be recognized as well-known. A trademark qualifies as “well-known” not by virtue of its ingenious design or successful registration, but rather through its long-term, extensive, and large-scale use in the market. Such use continuously enhances its reputation, enabling it to transcend the limitations of its original product class and become a household name.

Recognizing a well-known trademark is a complex and stringent legal process, the core of which lies in submitting sufficient and high-quality evidence. In cases claiming protection for a well-known trademark, there are extremely high requirements regarding the duration, scope, and intensity of the trademark's use. Typically, the applicant needs to provide proof across multiple dimensions, including but not limited to: the duration of continuous use of the trademark, market reputation, the reach of advertising, and consumer recognition.

Specific forms of evidence, besides traditional materials such as sales contracts, invoices, and advertising data, also include supplementary proofs like industry reports, market research data, awards received, and media coverage. Particularly important is that the evidence must demonstrate sufficient duration and broad geographic coverage, proving that the trademark has been used continuously over a long period and across wide areas, and has gained significant influence. The quality and completeness of the evidence directly impact the outcome of the recognition.

The Trademark Examination and Adjudication Guidelines explicitly stipulate that to apply for the recognition of a registered trademark in China as well-known trademark, the applicant shall provide materials proving that the trademark has been registered for not less than three years or used continuously for not less than five years. The overseas materials submitted shall be capable of proving that the trademark is known to the relevant public in China.

Therefore, when applying for the recognition of a well-known trademark, enterprises should systematically organize and comprehensively prepare relevant evidence in advance, ensuring it is thorough, detailed, and persuasive to meet the stringent requirements of the examination authority.

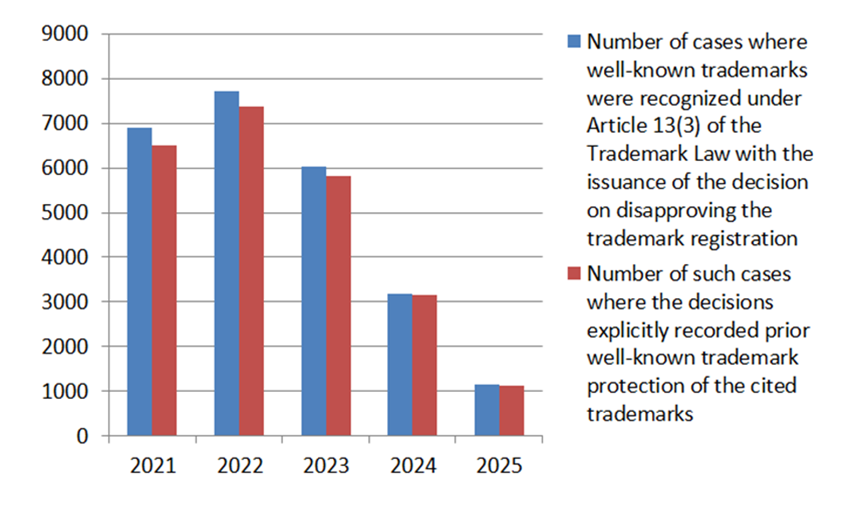

Meanwhile, statistics from the Mozlen database (as of September 22, 2025) indicate that in recent opposition cases involving the recognition of well-known trademarks, if the trademark in question has a prior record of being protected as a well-known trademark, it is more likely to be recognized as such again. For instance, in the opposition cases for trademark applications No. 77228728 “Yu bai jie bi rou(昱白洁碧柔)”ii, No. 75672461“SK-IK”iii, and No. 77404972 “NSKA”iv, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) again granted well-known trademark protection to Kao Corporation’s “碧柔(Biore)” trademark, Procter & Gamble’s “SK-II” trademark, and NSK Ltd.’s “NSK” trademark, all of which had previously received such protection.

For such trademarks, the burden of proof regarding their reputation is correspondingly reduced. If the scope for which well-known trademark protection is sought again is substantially the same as the scope for which it was previously protected, and the holder submits evidence demonstrating that the trademark’s well-known status from the prior case extends to the current case, well-known trademark protection is typically granted again.

3. Shield against “Bad-Faith Squatting”

While the current Trademark Law primarily focuses on protecting the exclusive rights of registered trademarks, it also provides a certain degree of protection for unregistered trademarks under specific circumstances, to prevent unfair competition, maintain fair market order, and uphold the principle of good faith. For unregistered trademarks, prior use is an essential prerequisite for obtaining protection. Below, we explore this in detail with reference to Articles 15 and 32 of the Trademark Law.

(1) Article 15 of the Trademark Law

Pursuant to this article, any person who, by virtue of an agency, representation, or other contractual or business relationship, has actual knowledge of another party’s trademark is prohibited from preemptively registering such trademark. The legislative intent is to combat bad faith registrations by parties in a special relationship, based on the principle of good faith.

Paragraph 1 of this article stipulates: “Where an agent or representative registers, in his or her own name, the trademark of a principal or represented party without authorization, and the principal or represented party raises an objection, the trademark shall not be registered and its use shall be prohibited.” Literally, this provision does not explicitly require that the principal’s or represented party’s trademark has been used. Does this mean that protection can be granted without the requirement for use?

According to the Trademark Examination and Adjudication Guidelines, the principal’s trademark includes not only “the trademark of the principal as stated in contracts or authorization letters,” but also “the trademark that the principal has already used on the goods or services for which they are being represented, at the time the agency relationship is established.” Similarly, the represented party’s trademark includes “the trademark that the represented party has already used, as well as other trademarks legally belonging to the represented party.”

Thus, in the absence of any agreement between the parties, “prior use” becomes an important consideration in the determination of whether a sign constitutes the trademark of the principal or represented party. The ability to prove such prior use is decisive in qualifying the sign as the trademark of the principal or represented party.

Paragraph 2 of the same article explicitly stipulates “prior use” as one of the applicable requirements. That is, the party should not only prove the existence of “contractual, business relationship, or other relationships beyond those specified in the preceding paragraph,” but also simultaneously prove the prior use of the said party's trademark. The scope of “prior use” here is broad, encompassing not only the use of the trademark on goods actually sold or services provided but also including promotional activities for the trademark, as well as substantive preparatory activities undertaken by the prior user to bring goods or services bearing the trademark to market.

Furthermore, the prior user need only prove that the trademark has been used, but not that it has acquired a certain degree of influence through use. In other words, the threshold for proving “prior use” under this clause is very low. Meeting the standard of proof essentially requires showing that the squatter, aware of the trademark’s existence due to the specific relationship, failed to voluntarily avoid it.

For instance, in the invalidation case concerning the trademark “豪使HEUSCHLAA CHEN H193588 MADE IN XTNHONG & device” (No. 43153036)v, the court held that the evidence on record could prove that the applicant had used the mark “HEUSCH AACHEN & device” on goods like spiral cutter blades for sheep shearing machines before the filing date of the disputed trademark. The respondent (the registrant of the disputed trademark) had long been engaged in selling the applicant’s cutting tools, and its legal representative had repeatedly placed orders for the applicant's products via WeChat and was aware, through WeChat conversations, that the applicant actually used the “HEUSCH AACHEN & device” mark on cutting tool goods. Under these circumstances, the respondent failed to voluntarily abstain from applying for the registration of the disputed trademark, and this act violated Article 15(2) of the Trademark Law.

This case also reflects that new types of electronic evidence, such as WeChat chat records, are increasingly becoming crucial elements in current litigation proceedings. Supported by real-name authentication and information technology, such evidence can sometimes directly determine the findings on disputed facts in a case, and serve as a core basis for judges' acceptance and recognition of the evidence.

(2) Article 32 of the Trademark Law

This article is one of the core provisions in the current trademark law system for protecting unregistered trademarks. It stipulates that an application for trademark registration shall not use unfair means to preemptively register a trademark that has been used by another person and has attained a certain degree of influence. The “use” referred to herein directly creates a prior right protected by law. Applying this article requires proving that another party’s trademark has been used and has attained a certain degree of influence; that is, use is a prerequisite. Compared to Article 15, this article imposes a higher requirement for use, necessitating proof that it has reached a level of “certain influence.” Once it is proven that the trademark has been used and has attained a certain influence, it can be presumed that the applicant was aware of the trademark and acted in bad faith.

It is important to note that, due to the territorial nature of trademark rights, the “prior use” mentioned here refers to actual use within the territory of mainland China. For instance, in the opposition case concerning the trademark “BEARINGTON COLLECTION” (No. 6747812)vi, the court held that the letter of authorization, cargo shipping consignment note, packing list, and product inspection report submitted by the opponent, Jiedi Inc., were self-made evidence. In the absence of corroborating third-party evidence such as customs declaration forms, their probative value was limited. Even if the authenticity of this evidence was accepted, it could only prove that Jiedi Inc. exported goods bearing the “BEARINGTON COLLECTION” trademark to the United States, but could not prove the reputation of the trademark within mainland China. Therefore, it was insufficient to establish that the application for the disputed trademark constituted “preemptive registration through unfair means of a trademark used by another party that has attained a certain influence.”

Similarly, in the invalidation case concerning the trademark “茶の魔手Chade mo shou” (No. 18572454)vii, the court also determined that use in other countries and regions cannot form the factual basis for obtaining relevant legal protection within mainland China. As the invalidation applicant only submitted evidence of use of the “茶の魔手” trademark in the Taiwan region and no evidence of use in mainland China, and given that the Taiwan region and mainland China belong to different legal jurisdictions, the registration of the disputed trademark did not constitute “preemptive registration through unfair means of a trademark used by another party that has attained a certain influence.” Likewise, in the invalidation case concerning the trademark “StAPLe” (No. 5172626)viii, the court affirmed that the scope of rights, content of protection, and term of protection of trademark rights are all limited by territorial scope. Actual use of a trademark within China requires that the commercial use of the trademark in actual business activities occurs within the territory of China, i.e., mainland China.

Through the above analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn: “Use” is the crucial link proving the bad faith of the squatter and the prior right of the rights holder. For unregistered trademarks, protection can typically only be sought through subsequent relief procedures such as opposition or invalidation. The law provides a limited, passive, and case-specific form of protection for them. Therefore, for enterprises, promptly applying for trademark registration remains the most fundamental and effective way to obtain the strongest legal protection and avoid potential legal risks. The protection of unregistered trademarks should be regarded as a necessary supplement and remedy, not the preferred option for establishing rights.

III. The Role of Trademark Use in Trademark Infringement Defenses

Trademark use constitutes a prerequisite for finding trademark infringement. Determining whether an accused act constitutes “trademark use” serves as the first threshold and logical starting point in trial of trademark infringement cases. Only after it is determined that the accused act constitutes trademark use will the court proceed to assess, based on factors such as the specific manner, scale, context, and subjective intent of the use, and using the “likelihood of confusion” as the standard, whether infringement ultimately exists. Trademark use also plays a significant role in the defense stage of infringement proceedings. Below, I will discuss the role of trademark use in defenses against trademark infringement by reference to Articles 59 and 64 of the Trademark Law.

1. Fair Use Defense

Article 59, Paragraph 1 of the Trademark Law stipulates that if a registered trademark contains descriptive elements, such as generic names, words or symbols indicative of the goods' contents or characteristics, or geographical names—the trademark owner cannot prohibit others from fairly using them. This provision aims to prevent trademark owners from monopolizing descriptive terms that rightfully belong to the public domain, thereby hindering other businesses from accurately describing their own goods or services. Paragraph 2 of the same Article states that if a three-dimensional registered trademark consists of a shape resulting from the nature of the goods themselves, a shape necessary to obtain a technical effect, or a shape that gives substantial value to the goods, the trademark owner cannot prohibit others from fairly using it. In other words, if a three-dimensional sign is functional, it should not be granted perpetual protection through trademark rights.

Indeed, descriptive terms often lack inherent distinctiveness and are generally unregistrable as trademarks; the same applies to functional three-dimensional marks. In practice, however, some originally non-distinctive marks may acquire distinctiveness through long-term use and thus become registered. There are also cases where a mark gains overall distinctiveness and becomes registrable by being combined with other distinctive elements. In trademark infringement disputes involving such registered marks, if the accused use is not “trademark use” intended to identify the source of goods or services, but rather “descriptive use” to describe the characteristics of the goods themselves, such use is “justified” and falls outside the scope of infringement under the law.

In such cases, key considerations for determining infringement typically include: the manner of trademark use (whether it is prominent, or used in its “primary meaning,” i.e., descriptive sense), subjective intent (whether there is an intent to free-ride on the right holder’s trademark's reputation, or whether the use is reasonable and in good faith), and industry practices (whether such usage is common and necessary).

In the “全波段” (Full Band) sun protection clothing trademark infringement disputeix, the defendant used the term “全波段防晒” (full band sun protection), which fully incorporated the plaintiff’s registered trademark “全波段.” Evidence showed that, prior to the plaintiff’s trademark registration, various stakeholders in the sun protection industry—including operators, consumers, marketers, and researchers—had widely used “全波段防晒” as a descriptive term for the function of sun protection products for nearly 20 years, a practice that continues to this day. Additionally, the plaintiff itself had used “全波段防晒” to describe the functionality of its sun protection clothing. The defendant did not use the term “全波段” prominently and provided an explanation below the term describing what “全波段防晒” means, while also clearly displaying its own trademark on the product packaging. The court therefore ruled that the relevant public would understand “全波段防晒” as describing the product’s function, not as an indicator of its source. This would not cause confusion, and the defendant’s use did not exceed the necessary scope of describing or explaining the product’s function. There was no intent to free-ride on the reputation of the “全波段” trademark, and thus no trademark infringement was found.

In contrast, in the “大富翁” (Richman) trademark disputex, the evidence was insufficient to prove that “大富翁” was a generic name for chess game products or that it merely directly described the characteristics such as function and use of the designated goods. Furthermore, the defendant’s use of the “大富翁” sign was not for the purpose of using its inherent descriptive meaning to describe product features but constituted trademark use. Additionally, the plaintiff had previously filed a request to invalidate the defendant’s registered “赛和大富翁(Saihe Richman)” trademarkxi. The China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) invalidated the disputed mark on the grounds that it was similar to the plaintiff’s “大富翁” trademark and used on identical or similar goods. This indicated that the defendant should have been aware of the plaintiff and its “大富翁” trademark. The naming method of the defendant’s product links also reflected an intent to free-ride on the reputation of the “大富翁” trademark, demonstrating a lack of good faith. Taking all these facts into account, the court ruled that the defendant’s use constituted infringement.

2. Prior Use Defense

Article 59(3) of the Trademark Law establishes that a trademark which has been used prior to the registrant’s trademark registration and has acquired a certain influence may continue to be used within the original scope, and the registrant is not entitled to prohibit such use. While the acquisition of trademark rights in China is primarily based on registration, there are a considerable amount of unregistered trademarks already in practical use. This legal provision reflects the protection afforded to “prior use” within the trademark registration system. The essential function of a trademark is to distinguish the source of goods. A prior user, through actual business operations, has accumulated goodwill, and this “de facto right” should also receive legal protection.

The successful establishment of the prior use defense herein requires the following conditions to be met: (1) The user had used the trademark and it had acquired a certain influence before the registrant filed the trademark application; (2) The trademark used is identical or similar to the registered trademark and is used on identical or similar goods; (3) The use by the trademark user does not exceed the original scope.

It is particularly important to note that the prior user's use must not only predate the filing date of the trademark registrant's application but also precede the time when the trademark registrant itself began using the mark. In the “老百姓大药房” (People’s Pharmacy) trademark infringement disputexii, the court explicitly stated that if the prior use, although earlier than the trademark application date, occurs after the registrant’s actual use of the mark, and there is evidence indicating that the prior user was aware or should have been aware of such use, the prior use defense should not be upheld. This case also emphasized that prior use must be in good faith, a view consistent with the stance of the Beijing Intellectual Property Court in the (2019) Jing 73 Civil Final No. 1106 trademark infringement casexiii, which held that unlawful use cannot generate protected rights, and illegal use does not constitute a prior use defense. In essence, the purpose of the prior use defense system is to protect the legitimate rights and interests derived from prior use by businesses operating in good faith. In the “双飞人” (Double Flying Man) trademark infringement and unfair competition disputexiv, the defendant’s product had acquired a certain influence through prior advertising, while the plaintiff, aware of the defendant’s product already being on the market, filed out of bad faith for registration of a trademark similar to the defendant’s product packaging and subsequently asserted rights based on this registration. In this regard, the Supreme People’s Court determined that the alleged infringement fell within the circumstances specified in Article 59(3) of the Trademark Law, and the trademark registrant had no right to prohibit the prior user from continuing use within the original scope. This demonstrates that when determining a prior use defense, the courts will also consider whether the subsequent trademark registration itself was filed in good faith.

Regarding “certain influence,” the Beijing High People’s Court’s “Several Legal Issues to Note in Current Intellectual Property Trial” clarifies that the threshold for the degree of influence should generally not be set too high. It is sufficient if the prior user’s use of the trademark is genuine and, through such use, the trademark has acquired a distinguishing function within its geographic area of use, thereby meeting the requirement of having “certain influence.”

Concerning the “original scope of use,” there is currently no precise judicial definition. The criteria for determining whether the use constitutes one within the original scope remain relatively ambiguous when the geographical scope, method, subject, or scale of use exceeds the original scope. In the “理想空间” (Ideal Space) trademark infringement disputexv and the “华联超市 (Hualian Supermarket)” trademark infringement disputexvi, the Supreme People’s Court pointed out that when determining the “original scope,” the focus should be on the geographical scope and specific manner of the trademark’s use. If the prior user initially sold goods or provided services only through physical stores, but after the trademark registrant applied for registration or began using the mark, the prior user opens new stores in regions beyond the influence scope of the original physical stores or switches to online or other new sales channels to sell goods or provide services, this would generally be considered as exceeding the original scope. In practice, depending on the specific circumstances of a case, interpretations from different perspectives may lead to varying conclusions. We believe it is essential to look beyond superficial appearances and base the core determination on the reach of the goodwill accumulated by the prior user through its use of the trademark.

3. Exemption from Compensation Liability

Article 64(1) of the Trademark Law stipulates that when a trademark registrant claims damages, the alleged infringer may defend themselves by arguing that the registrant has not used the registered trademark. If the registrant has not actually used the registered trademark within the previous three years, the alleged infringer is generally not liable for compensation.

The term “use” discussed in the previously mentioned “fair use defense” and “prior use defense” refers to the use by the alleged infringer. In contrast, the “use” discussed here refers to the use by the claimant (i.e., the trademark registrant). In practice, there are instances where trademarks are registered not for actual use but with the intent to either transfer them at a high price or initiate bad-faith litigation to claim damages. However, the fundamental purpose of the trademark legal system is to protect the distinguishing function of trademarks, prevent consumer confusion, and safeguard the commercial reputation accumulated by the registrant through use. A registered trademark that has not been put into use for a long time, although legally entitled to exclusive rights, is hardly recognized by the relevant public and lacks market awareness, thus failing to establish genuine market reputation or business value. Such registered trademarks often provide a weak basis for rights in infringement lawsuits, significantly diminishing the effectiveness of enforcement.

Article 64(1) of the Trademark Law elevates “trademark use” from a statutory post-registration obligation to a key fact in determining compensation liability in infringement litigation. This provision effectively prevents trademark right holders who lack a genuine intent or action to use the trademark from obtaining improper benefits through litigation, thereby maintaining fair market competition. For the alleged infringer, this clause serves as a “shield” against bad faith litigation and the abuse of rights; for the trademark owner, it is a warning that the trademark must be put into genuine business activity, otherwise, their rights may “fail” at critical moments of enforcement.

It is important to note that invoking this article for a defense can only exempt the alleged infringer from compensation liability, but hardly alter the nature of the infringement. If the court rules that infringement has occurred, the alleged infringer remains liable for legal responsibilities such as ceasing the infringement and eliminating its effects.

Conclusion

This article systematically reviews and analyzes the pivotal role of “trademark use” in trademark authorization, determination, and infringement defenses, referencing relevant provisions of the current Trademark Law and typical cases. We can draw the following conclusion: as a commercial sign distinguishing the source of goods or services, the core value of a trademark lies in its actual use. “Trademark use” is a lifeline running through both the theory and practice of trademark law. With the continuous optimization and improvement of the trademark legal system, the mindset of “emphasizing registration over use” is being fundamentally reversed. The foundational status of trademark use within the trademark system is becoming increasingly prominent and is bound to be further strengthened.

————————————————————————————————————————————

References:

i Judgment of Beijing High People’s Court (2018) BJ Administrative Final No. 3673

ii Decision on the Disapproval of Registration of Trademark “昱白洁碧柔”(No. 77228728)

iii Decision on the Disapproval of Registration of Trademark “SK-IK” (No. 75672461)

iv Decision on the Disapproval of Registration of Trademark “NSKA” (No. 77404972)

v Administrative Ruling of the Supreme People’s Court (2024) SPC Administrative Retrial No. 6775

vi Judgment of Beijing High People’s Court (2017) BJ Administrative Final No. 491

vii Judgment of Beijing High People’s Court (2019) BJ Administrative Final No. 4875

viii Administrative Ruling of the Supreme People’s Court (2023) SPC Administrative Retrial No. 2567

ix Judgment of Shanghai Intellectual Property Court (2023) SH 73 Civil Final No. 285

x Judgment of Ningbo Intermediate People’s Court of Zhejiang Province (2025) Zhe 02 Civil Final No. 1584

xi Decision on Invalidation of Trademark “赛和大富翁” (No. 25576999)

xii Judgment of the Supreme People’s Court (2024) SPC Civil Final No. 218

xiii Judgment of Beijing Intellectual Property Court (2019) BJ 73 Civil Final No. 1106

xiv Judgment of the Supreme People’s Court (2020) SPC Civil Retrial No. 23

xv Judgment of the Supreme People’s Court (2018) SPC Civil Retrial No. 43

xvi Judgment of the Supreme People’s Court (2021) SPC Civil Retrial No. 3