Meiyan LI

Attorney-at-Law

Beijing Wei Chixue Law Firm

Attorney-at-Law

Beijing Wei Chixue Law Firm

Introduction

Article 10(1)(vii) of the China Trademark Law provides that a sign “having the nature of deception and being apt to mislead the public as to the quality or other characteristics or the origin of the goods” shall not be used as a trademark. In judicial practice, the number of cases of rejection of trademark applications for violation of this deceptiveness clause is increasing year by year. This article provides compliance guidelines and defense approaches for trademark applicants by sorting out the statistical data of refusal and review cases involving this clause, analyzing judicial determination standards, and exploring defense strategies based on practical experience.

I. Statistical analysis of review of refusal cases involving Article 10(1)(vii) of the China Trademark Law

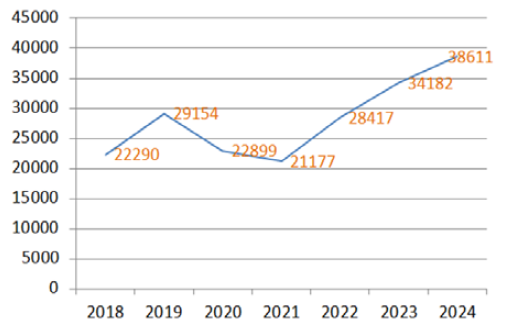

According to the Mozlen database, the number of decisions of review of refusal involving Article 10(1)(vii) of the China Trademark Law as a whole is shown in the figure below, which has been steadily increasing since 2022 and reaching 38,611 in 2024, accounting for 14.8% of the total number of review of refusal decisions in that year, reflecting the continuous strengthening of examination of the absolute prohibition situations involved in Article 10 in trademark examination.

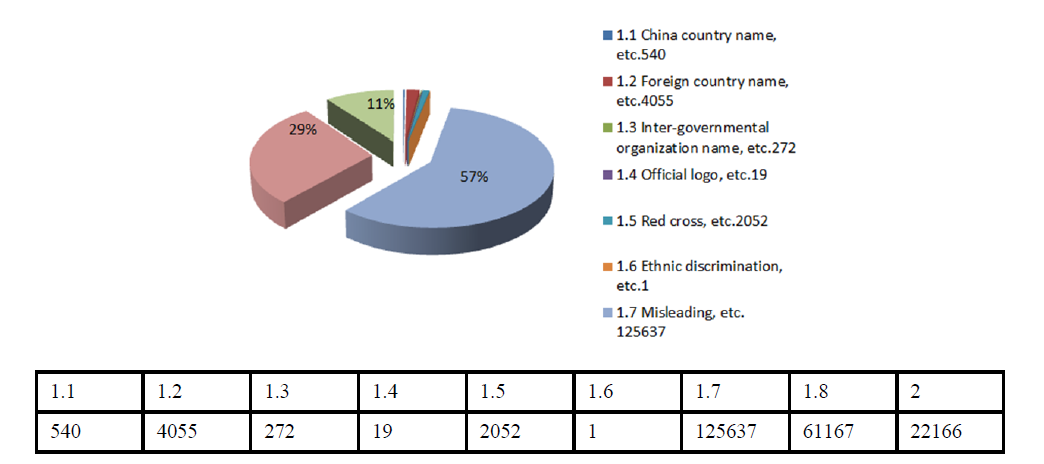

The proportion of specific items (i.e., Article 10, paragraph 1 (i) to (viii) and Article 10, paragraph 2) of the Trademark Law is as follows, of which the number of cases involving Article10(1)(vii) is 125,637, accounting for 57%, far exceeding other provisions and becoming the most frequently applied provision in Article 10.

Note: Data from 2016 to May 12, 2025

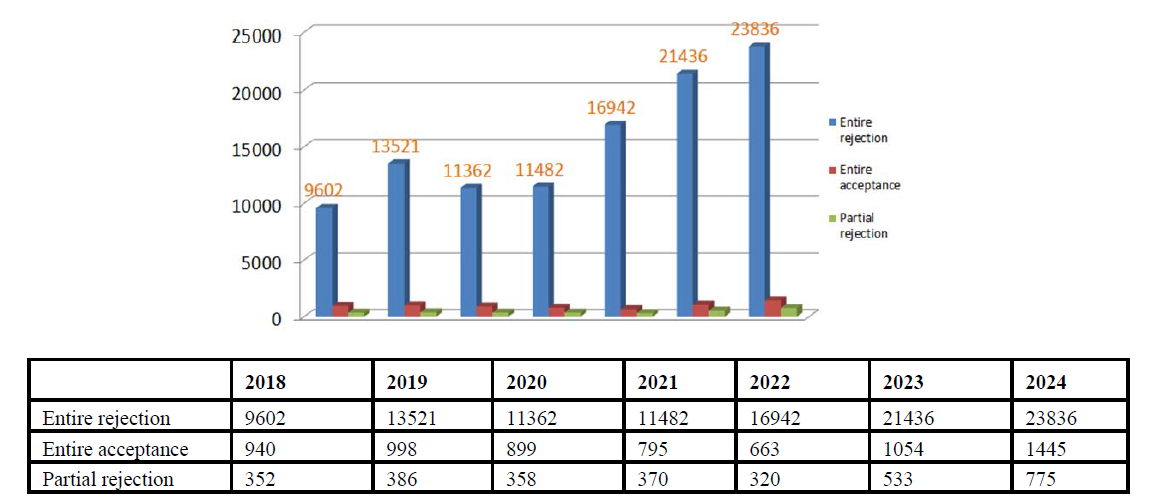

Looking at the outcomes of review of refusal decisions involving Article 10(1)(vii), “entire rejection” accounts for the largest share, followed by “entire acceptance,” while “partial rejection” represents the smallest proportion. This shows that trademarks refused under Article 10(1)(vii) have only a slim chance of securing preliminary approval upon review, underscoring the provision’s rigorous application in practice.

Statistics of review of refusal decisions involving Article 10(1)(vii)

II. Judicial Criteria for Article 10(1)(vii) of the China Trademark Law

The 2021 Trademark Examination Guidelines define “deceptiveness” as any representation by a sign that exceeds the inherent qualities or origin of the designated goods or services, or is factually inaccurate, and is therefore likely to mislead the public as to the quality, characteristics, or origin of the goods or services. Examples include using “healthy” or “longevity” on cigarettes, or “all-purpose” on pharmaceuticals.

Although the law itself does not provide detailed standards for applying the deceptiveness clause, a systematic set of application rules has been developed through implementing regulations, departmental rules, judicial interpretations, and examination guidelines. Combined with the application of a number of precedents, when determining whether a trademark in question constitutes the circumstances specified in Article 10(1)(vii), it should be determined from the following two aspects based on the general knowledge and cognitive capacity of the public within China, taking into account the goods or services designated by the trademark:

(1) Inherent deceptiveness of the sign: the meaning, appearance, or other elements of the sign are inconsistent or not completely consistent with the quality, function, intended use, raw materials, or other characteristics—or the origin—of the designated goods.

(2) Consequence of deceptiveness: the sign’s deceptive nature is sufficient to cause the relevant public to form an erroneous impression regarding the goods’ characteristics or origin.

In judicial practice, courts usually focus on the first element: if they find the disputed mark inherently deceptive, they will readily presume that it is “likely to mislead.” Nevertheless, if the public would not be misled based on everyday experience, the clause does not apply. For example, in the administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case (2023) Jing Xing Zhong No. 8393, the Beijing High People’s Court held that the disputed mark was used on goods such as “rice; rice with gluten,” and combined with the meaning of the dominant part “金椰子” (“Golden Coconut” in English) of the mark

, the raw materials and ingredients usually used or contained in the “rice, rice with gluten,” and the general knowledge and cognitive capacity of the relevant public, the mark alone was insufficient to cause the relevant public to form an erroneous impression about the goods’ flavor, variety, or raw materials. Accordingly, the court declined to apply Article 10(1)(vii).

, the raw materials and ingredients usually used or contained in the “rice, rice with gluten,” and the general knowledge and cognitive capacity of the relevant public, the mark alone was insufficient to cause the relevant public to form an erroneous impression about the goods’ flavor, variety, or raw materials. Accordingly, the court declined to apply Article 10(1)(vii). III. Defense strategies against Article 10(1)(vii) of the Trademark Law

As mentioned above, the success rate of review of refusal involving Article 10(1)(vii) of the Trademark Law is relatively low. For important signs that are significant to a company’s development, trademark applicants can continue to seek relief through administrative litigation. Although no authoritative statistics exist on the success rate of such litigation, practical experience indicates that prevailing against this provision remains difficult overall. Defense strategies must be tightly aligned with the judicial criteria, with the core argument being that the disputed trademark's meaning aligns with the inherent attributes of the goods, thereby eliminating the possibility of public misrecognition. It can be elaborated in the following aspects:

1. Overcoming “deceptiveness” by abandoning goods unrelated to the meaning conveyed by the disputed mark

The determination of deceptiveness must be assessed in relation to the designated goods designated by the disputed mark. If the mark’s use on certain goods will not mislead the public, registration for those goods may be approved. In other words, when the meaning of the mark aligns with the inherent nature of the designated goods, the possibility of public misapprehension is eliminated and the deceptiveness clause would not be applied. This approach is especially critical for marks that incorporate the name of a raw material.

For example, in the administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case (2022) Jing Xing Zhong No. 1576, the Beijing High People’s Court held that the mark “肉联帮” (“Meat Union Group” in English) used on “meat; canned meat” did not make any deceptive representation about the goods’ characteristics and therefore did not violate Article 10(1)(vii). However, when the same mark was used on “pickled fruit,” the court found it likely to mislead the public as to the goods’ ingredients or composition, bringing it within the scope of Article 10(1)(vii).

When adjudicating deceptiveness, courts are required to analyze each designated good individually; hence, deleting or abandon certain goods should not affect the deceptiveness analysis for the remaining goods. From a practical standpoint, however, the author’s suggestion is to abandon goods unrelated to the raw material referenced in the mark, thereby narrowing the dispute to the relevant goods. This clarifies the scope of examination and signals to the court the applicant’s determination to strive for trademark registration. In an administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case handled by the author, the disputed mark contained the chemical element “氢” (“hydrogen” in English). At the time of filing suit, the plaintiff (trademark applicant) limited the goods specification to “hydrogen fuel cells” and abandoned all other goods. The court ultimately held that the descriptiveness of “hydrogen” matched the raw-material characteristics of the goods and therefore the mark was not deceptive. Similarly, in the administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case (2021) Jing Xing Zhong No. 7407, after the plaintiff (trademark applicant) abandoned goods unrelated to “cocoa,” the court determined that the mark “可可联盟” (“Cocoa Alliance” in English) would not mislead the public when used on “cocoa; cocoa powder; chocolate sauce.”

It should be noted that the effect of abandoning some goods in administrative litigation has not yet formed a unified judicial standard. In some cases, it is held that if the administrative organ has not made a decision regarding the deletion of goods, the court should not directly recognize the waiver of the goods in the lawsuit. However, in some cases, it was determined that after the applicant abandoned some of the goods, the refusal decision of these goods had taken effect, and only the remaining goods needed to be adjudicated. In order to reduce the risk, it is recommended that the applicant delete the goods that may cause misapprehension at the stage of refusal review, and if they do not do so in time, they can submit an application for deletion to the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) at the same time as filing an administrative lawsuit, which usually takes 1-2 months to be approved.

2. Chinese part of International Registrations may overcome “deceptiveness” by amending the description of goods.

For marks that include a chemical element (or similar term), even when the specifications are limited to related goods, the marks may still be deemed deceptive. In such cases, the applicant can modify the wording of the goods to make it explicit that those goods do, in fact, contain the element referenced in the disputed mark, thereby eliminating any possibility of public misapprehension.

In a case handled by the author, the disputed mark contained the chemical element “Ti” (titanium) and was rejected on grounds of deceptiveness. The applicant narrowed the goods description to “goods containing titanium” via filing a request with the International Bureau. Although the CNIPA maintained, at the review of refusal stage, that the mark was deceptive, the court held that the descriptive meaning of “Ti” consisted with the raw-material characteristics of the designated goods and would not mislead the public. Consequently, the court found that the mark was not deceptive.

Thus, for marks that are refused on the ground of containing a chemical element (or similar term), amending the goods description can effectively preclude the application of the deceptiveness clause. It should be noted, however, that for domestic Chinese applications, the CNIPA conducts a strict formal examination of the description of the designated goods; such amendments are usually not accepted. By contrast, the applicants can amend or restrict the goods description for the Chinese part of the international registrations by filing MM6 (limitation) under Madrid System.

Moreover, in cases where the applicant has submitted evidence showing that the goods in use actually contain a particular raw material, yet the application is rejected on the ground that “it cannot be guaranteed that future goods will necessarily contain that raw material,” the applicant may—provided the mark is an international registration—try to overcome the deceptiveness clause by amending the goods description to specify that the goods contain the particular raw material.

3. Overcoming “deceptiveness” by submitting evidence of use

(1) Eliminating the possibility of misapprehension through evidence of use

Does the actual use of a mark help remove the obstacle posed by the deceptiveness clause? The CNIPA’s position is inclined to treat Article 10(1)(vii) of the Trademark Law as an absolute prohibition; in its view, the registrant cannot overcome the obstacle by relying on actual use of the sign. In judicial practice, however, the courts have not yet achieved a unified view, and the issue must be analyzed case by case. In the author’s opinion, submitting evidence of use can play a positive role in eliminating the obstacle to registration.

In the administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case (2021) Jing Xing Shen No. 2030, the Beijing High People’s Court held that Qia Qia Company’s use of the disputed mark “坚果先生” (“Mr. Nuts” in English) could not overcome the absolute prohibition. By contrast, in the administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case (2022) Jing Xing Zhong No. 1898, the same court considered that “国窖班” (“National Cellar Class” in English) did not, as a whole, describe the quality of the goods, and that the mark “国窖” (“National Cellar” in English) already enjoyed a certain reputation; therefore, the public would not be misled, and the court ultimately approved its registration. In both cases the issue was whether evidence of use could overcome the deceptiveness clause, yet the Beijing High People’s Court reached opposite conclusions. Although the mark in the case (2022) Jing Xing Zhong No. 1898 did not concern raw materials, the determination nonetheless shows that evidence of use can play a positive role in overcoming the deceptiveness clause.

Further, in the administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case (2025) Jing Xing Zhong No. 1874, the plaintiff (trademark applicant) argued that its series marks of “极氪” (corresponding English brand is “Zeekr”, the Chinese character “氪” refers to chemical element “krypton”) used on automobiles and other goods had already formed a stable association and market recognition with Geely Company, and that no “deceptive” situation had ever arisen. The Beijing High People’s Court also found that the evidence on record demonstrated that the “极氪” brand had been extensively promoted both domestically and internationally, had actually been placed on the market, had acquired a certain reputation in respect of automobiles, and had not caused the public to be misled as to the raw materials or ingredients of the goods. Consequently, the disputed mark “极氪X” on the goods subject to the review did not violate Article 10(1)(vii) of the Trademark Law. This case further illustrates that, even when the deceptiveness clause is at issue, evidence of the mark’s use can play a positive role in eliminating the possibility of misapprehension. Therefore, for marks that have gained a certain influence through use, every effort should be made to collect and submit evidence of use.

(2) Overcoming deceptiveness by submitting test reports

In the retrial of administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case (2019) Zui Gao Fa Xing Zai No. 249, the Supreme People’s Court held: “According to the evidence submitted by Wuhan Lizhi Company, the product formula of the goods on which the applied-for mark is used contains rock sugar and honey. Judged solely from the sign “肾源春冰糖蜜液” (“Shenyuan Chun Rock-Sugar Honey Liquid” in English) itself, it is not sufficient to conclude that the mark’s use on the designated goods will cause the relevant public to form an erroneous impression about the goods’ raw materials or ingredients; it is therefore difficult to deem the mark deceptive to the public.” In that case the applicant submitted a product function test report for the goods “肾源春冰糖蜜液” and a toxicological safety test report—i.e., the applicant overcame the deceptiveness objection by furnishing evidence proving that the designated goods actually contain the raw materials referred to in the disputed mark.

Although Article 10(1)(vii) of the Trademark Law is an absolute prohibition clause for trademark use, the author believes that the applicant may attempt to overcome the deceptiveness objection by submitting test reports or similar documents, or by submitting extensive, high-quality evidence of use demonstrating that the mark has been used in the market for a long time, on a large scale, and in a standardized manner, thereby establishing a stable market order in which the relevant public recognizes the sign as a trademark and is not misled about the raw-material characteristics of the designated goods—thus breaking through the limitation imposed by the deceptiveness clause.

4. Asserting that the mark as a whole does not describe characteristics such as raw materials

For marks that incorporate uncommon chemical elements, the applicant may argue that the mark, taken as a whole, possesses no descriptive meaning with respect to the goods’ raw materials or other characteristics, thereby precluding application of the deceptiveness clause.

In the above mentioned case (2025) Jing Xing Zhong No. 1874, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court held at first instance that the disputed mark “极氪X” contains the chemical element “氪” (krypton) and, when used on the designated goods under review, was likely to mislead the relevant public into associating the goods’ principal raw materials or ingredients with that element. At the second instance, the trademark applicant contended that the mark must be viewed holistically and that “极氪” is a coined word devoid of any descriptive meaning relating to the goods’ raw materials or other characteristics. For this argument, the Beijing High People’s Court held: “Although ‘氪’ is a chemical element, the Chinese characters ‘极氪,’ when used as a trademark on the goods requested for review such as ‘motorcycles; automobiles; automobile chassis,’ will not, in light of the public’s everyday experience and ordinary level of knowledge, readily be associated with the principal raw materials or ingredients of those goods, and therefore will not cause misapprehension.”

Similarly, in the administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case (2016) Jing Xing Zhong No. 2384, the Beijing High People’s Court held that the disputed mark is a combination of characters “肽帅” (the first character could mean “peptide”) and, taken as a whole, has no specific meaning. Even if the goods on which the applied-for mark is used do not contain the chemical raw material specifically denoted by “肽 (peptide),” the mark cannot, on that account, be deemed deceptive in its entirety. Likewise, in the administrative dispute over review of trademark refusal case (2018) Jing 73 Xing Chu No. 13085, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court determined that trademark No. 26252896, consisting of the characters “肽嫩” together with a device, has no specific meaning as a whole. When designated for use on goods such as “cosmetics; facial cleansers; dish-washing detergents; abrasives; leather oils; essential oils,” the absence of the chemical raw material denoted by “肽 (peptide)” in the goods does not render the disputed mark deceptive overall.

To sum up, for marks containing chemical or other elements, if the mark does not describe characteristics such as raw materials and the public, based on everyday experience, is unlikely to be misled, the applicant may assert that the mark, viewed as a whole, is not deceptive and will not engender public misapprehension.

IV. Conclusion

Due to space constraints, this article has only taken marks containing product ingredients as its entry point to explore the avenues of defense against the deceptiveness clause. The strategies proposed herein are distilled from practical experience with the most frequent issues encountered in trademark prosecution and adjudication. In specific cases, it is still necessary to formulate the most effective defense strategy based on the characteristics of the specific trademark and designated goods. At the same time, it should be borne in mind that the inherent distinctiveness of the sign itself is equally critical; even if the deceptiveness clause is successfully overcome, a mark that lacks distinctiveness may still be refused for registration.

The author believes that the examination and application of Article 10(1)(vii) of the Trademark Law should be applied with circumspection. Under the current statute, once a mark is found deceptive, its very use becomes punishable. Consequently, the clause should be confined to situations where misapprehension has in fact been caused and is of a sufficiently serious degree.

Although the success rate for overcoming rejections based on the deceptiveness clause is low and administrative litigation presents certain obstacles, an applicant whose core mark is at stake should nonetheless exhaust every possible avenue of defense. Doing so may enable the mark to break through the impasse and regain its value.