Yu GAO

Attorney-at-Law

Trademark Attorney

Beijing Wei Chixue Law Firm

Attorney-at-Law

Trademark Attorney

Beijing Wei Chixue Law Firm

I. Introduction

On December 11, 2001, China officially joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). To fulfill the obligations under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement) upon accession to the WTO, China revised the Trademark Law in the same year, officially including “three-dimensional signs” in the scope of registrable application signs. This marked the formal establishment of China's legal protection system for three-dimensional trademarks. Article 8 of the revised Trademark Law clearly stipulates by way of enumeration that "three-dimensional signs" and other two-dimensional elements belong to the registrable trademark components. Currently, the legal framework regulating the examination of three-dimensional trademarks in China mainly consists of Article 12 (exclusion of functionality) of the current Trademark Law and other general provisions, Article 13 (application form requirements) and Article 43 (examination of three-dimensional trademarks) of the Implementing Regulations of the Trademark Law, Chapter 6 of the Volume Two of the Trademark Examination Guidelines (specific rules and standards for the examination of three-dimensional trademarks), and Article 9 of the Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Several Issues Concerning the Trial of Administrative Cases of Trademark Granting and Confirmation of Rights (judgment of the distinctiveness and functionality of three-dimensional trademarks), etc.

As the longest-introduced type of non-traditional trademark, three-dimensional trademarks are still relatively less accepted in China's registration practice. This is specifically manifested in limited total applications, a low granting rate, lack of clarity and unity in examination and adjudication standards, and frequent disputes in the examination practice. In the examination of three-dimensional trademarks, non-functional examination and distinctiveness examination are the focus and difficulties. Functionality or lack of distinctiveness is the main reason for the rejection of three-dimensional trademarks for commodity shape or packaging containers, and it is also a point that is prone to disputes in practice. At present, our country's examination standards in these two aspects are still vague, lack of specific application paths, and need to be further clarified and refined. The author of this article tries to put forward some suggestions for improvement through comparative studies.

II. Clarifying the Examination Standards for the Non-functionality of Three-Dimensional Trademarks

1. Factors of consideration in the Examination of the Non-functionality of Three-Dimensional Trademarks in China

Compared with two-dimensional trademarks, non-functionality is a unique requirement for the registration of three-dimensional trademarks. Article 12 of China Trademark Law specifically stipulates the non-functionality examination of three-dimensional trademarks. The main legislative purposes of this provision are “to maintain fair competition, promote technological progress, and boost the development of the trademark cause1”, as well as “to safeguard the public domain in trademark law, prevent the permanent monopoly of configuration s that may promote technological progress through trademark registration, and thus hinder technological development and the public’s use of technology2”. The Trademark Examination Guidelines (hereinafter referred to as the “Guidelines”) explained the key points of the non-functionality examination of three-dimensional trademarks through examples. However, the explanations in the Guidelines are still rather abstract, and it is difficult to grasp the specific application standards.

In the examination practice of three-dimensional trademarks, it is relatively rare for the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) to reject registration applications by applying Article 12 of the Trademark Law. The reason may be related to the ambiguity of the examination standards set by this provision.

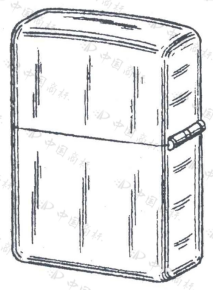

In judicial practice, in the “lighter three-dimensional trademark” case3, the court established the following judgment rule: “If the shape of a three-dimensional sign is indispensable for the use or purpose of a product, or affects the cost or quality of the product, then the shape has functionality; furthermore, when the shape characteristics exclusive to a trademark applicant put other competitors in the same industry at a significant disadvantage unrelated to the applicant's goodwill, the shape of the applied-for trademark constitutes a functional shape. The existence of alternative designs usually proves that the shape of the applied-for trademark does not have functionality, but the alternative designs need to have an appearance that is basically similar to the shape of the applied-for trademark.” In this case, it was determined that “each key feature of the shape shown by the opposed trademark is necessary to achieve the technical effect and has functionality.”

[Three-dimensional trademark No. 3031816]

The above judgment proposed three key points for the non-functionality examination, namely: 1. Whether the shape design of the three-dimensional trademark is indispensable for the use or purpose of the product; 2. Whether this shape will put other competitors in the same industry at a significant disadvantage unrelated to the applicant’s goodwill; 3. Whether there are similar alternative designs.

In the “M&G pen three-dimensional trademark” case4, although the CNIPA believed that “(the applied-for trademark) has obtained a high level of popularity and reputation for the product and already has the necessary distinctiveness of a trademark”, it rejected the trademark registration application on the grounds that “this three-dimensional sign is only composed of the shape of the product necessary to achieve the technical effect”. The applicant was dissatisfied and filed an administrative lawsuit. The second-instance court finally determined that: “Pens adopting this three-dimensional shape can alleviate the friction between the user’s knuckles and the pen during use, enhancing the comfort of holding the pen. The design of the pen cap clip facilitates the carrying and fixing of the pen, improving the convenience of use. Even though the three-dimensional sign of the disputed trademark is different from other pen shape designs, such difference has not changed its overall form as a pen and its writing function. The fact that the three-dimensional sign of the disputed trademark adopts special designs such as pen clips and pen caps can only indicate that the disputed trademark may be protected by copyright law or patent law. It still consists of three-dimensional shapes necessary for making the inherent functions of the commodity easier to realize. When used on commodities such as fountain pens, it is functional and constitutes the ‘shape of a commodity necessary to obtain technical effects’ as referred to in Article 12 of the Trademark Law.” Based on this, the court upheld the review decision to reject the disputed trademark.

In the “M&G pen three-dimensional trademark” case4, although the CNIPA believed that “(the applied-for trademark) has obtained a high level of popularity and reputation for the product and already has the necessary distinctiveness of a trademark”, it rejected the trademark registration application on the grounds that “this three-dimensional sign is only composed of the shape of the product necessary to achieve the technical effect”. The applicant was dissatisfied and filed an administrative lawsuit. The second-instance court finally determined that: “Pens adopting this three-dimensional shape can alleviate the friction between the user’s knuckles and the pen during use, enhancing the comfort of holding the pen. The design of the pen cap clip facilitates the carrying and fixing of the pen, improving the convenience of use. Even though the three-dimensional sign of the disputed trademark is different from other pen shape designs, such difference has not changed its overall form as a pen and its writing function. The fact that the three-dimensional sign of the disputed trademark adopts special designs such as pen clips and pen caps can only indicate that the disputed trademark may be protected by copyright law or patent law. It still consists of three-dimensional shapes necessary for making the inherent functions of the commodity easier to realize. When used on commodities such as fountain pens, it is functional and constitutes the ‘shape of a commodity necessary to obtain technical effects’ as referred to in Article 12 of the Trademark Law.” Based on this, the court upheld the review decision to reject the disputed trademark.

[Three-dimensional trademark No. 36939797]

It can be seen that in fields where the expression space of product shape design is relatively limited, such as lighters, fountain pens and other products, the CNIPA and judicial organs have adopted strict examination standards for the non-functionality element of three-dimensional trademarks. If the overall design differences of a three-dimensional trademark do not change the core form of the product and still serve the main functions of the product, it may be determined that it is only composed of the product shape necessary to achieve the technical effect, thus having functional characteristics. But can this examination logic be applied to other types of products?

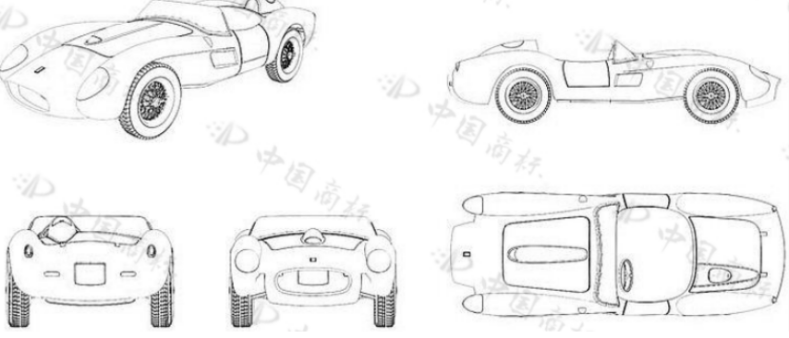

In 2024, in the sports car three-dimensional trademark registration application case, after examination, the CNIPA determined that the applied-for trademark lacked distinctiveness for goods “automobiles, etc.” in Class 12 and “scale model cars (toys), etc.” in Class 28, and rejected its registration application for violating the provisions of Item 3, Paragraph 1, Article 11 of the Trademark Law.

[International Registered trademark No. G1674041]

During the review stage, the CNIPA supplemented a ground of refusal, pointing out that “the applied-for trademark is only composed of the shape resulting from the nature of the product itself, the shape of the product necessary to achieve the technical effect, or the shape that gives the product substantial value. According to Article 12 of the Trademark Law, it cannot be registered as a trademark”, and served a notice of examination opinions on the applicant. In the subsequent review decision on trademark refusal, the CNIPA determined that: “The applied-for trademark is the three-dimensional sign of the applicant’s classic model ‘250 Testa Rossa’, which includes five perspectives of the car. It has a striking shark nose at the front and a streamlined rear wing at the rear. This model features a unique design, and both its name and shape themselves have strong originality. When used as a trademark on the designated goods, it has distinctive features and does not constitute the situation specified in Item (3) of Paragraph 1 of Article 11 of the Trademark Law.” However, this decision still maintained the original refusal conclusion, determining that “the applied-for trademark is only composed of the shape that gives the product substantial value”, so it still violated Article 12 of the Trademark Law5.

This case is very similar to the M&G pen case in the examination of the distinctiveness and non-functionality of three-dimensional trademarks, that is, it affirmed the distinctiveness of the three-dimensional sign but determined that the sign has functionality. It is worth noting that the review decision did not specifically demonstrate how the applied-for trademark constituted “the shape that gives the product substantial value”.

2. Consideration Factors in the Examination of the Non-functionality of Three-Dimensional Trademarks in the United States from the Sports Car Three-Dimensional Trademark Case

The author observed that the territorial extension application of the same International Registration in the United States was also rejected by The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), but was finally approved for registration after the applicant submitted a response. Similar to the examination practice in China, the refusal grounds of the US examiner were mainly based on the following two points6: 1. This sign constitutes the “functional design” of the product and does not meet the requirements for registration on the principal register; 2. The applied-for trademark lacks “inherent distinctiveness” and needs to prove through usage evidence that it has acquired distinctiveness. In the non-functionality examination of this case, the examiner explained the basic principles for the examination of the non-functionality of three-dimensional trademarks in the United States in the refusal notice: If a three-dimensional shape is “essential” to the use of the product, or constitutes the purpose of the product itself, or may affect the price and quality of the product, then the three-dimensional trademark has functional characteristics. The examiner also cited the “Morton-Norwich factors” as the exclusion criteria for non-functionality determination:

(1) The existence of a utility patent disclosing the utilitarian advantages of the design sought to be registered.

(2) Advertising materials of the applicant that tout the design’s utilitarian advantages.

(3) The availability to competitors of alternative designs.

(4) Facts indicating that the design results in a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.

If any of the above factors exist, it can be presumed that the sign has functionality and cannot be registered as a trademark.

In this case, the US examiner determined that the three-dimensional sign of the car had functionality based on the retrieved evidence. The logical argument was: The core function of a car is transportation (major premise) → The three-dimensional shape of the applied-for trademark serves the transportation purpose (minor premise) → Therefore, this shape constitutes the essential purpose of the product (conclusion). This argument directly equates the inherent function of the product with its shape characteristics, essentially denying the registrability of three-dimensional trademarks for car-type products and also undermining the value foundation of the three-dimensional trademark system. The author believes this point is debatable.

However, the applicant of this trademark made targeted defenses around the four-factor framework:

(1) Lack of model patent utility or design patent: Applicant has never filed a design patent application, and no design patent has issued, in connection with the Design Mark.

(2) Advertising does not highlight functionality: Applicant’s advertising materials outline the qualities of the engine (the engine is not within the scope of trademark protection).

(3) There are sufficient alternative designs: There are a large number of differentiated designs in the car market, and this shape is not necessary in the industry.

(4) Complex and expensive manufacturing process: The production cost of this design is significantly higher than that of ordinary sports cars, and registration will not force competitors to adopt high-cost processes.

Based on the above arguments, the applicant successfully overcame the refusal.

It can be seen that the non-functionality examination is crucial in the registration of three-dimensional trademarks. The legislative purpose of Article 12 of the Trademark Law is to prevent applicants from monopolizing common product shapes or technical solutions through the registration of functional three-dimensional signs, thereby suppressing market competition and technological development. However, in the examination practice, it is necessary to avoid overly simplifying the determination criteria; otherwise, the legislative value of the three-dimensional trademark system will be weakened. For the non-functionality examination of three-dimensional signs, it can be judged from multiple dimensions, such as whether the sign has practical value, the actual usage methods of the sign by the applicant, the existence of alternative designs, and the impact of the registration of three-dimensional trademarks on competitors in the same industry, so as to avoid overly strictly excluding product shapes from the scope of three-dimensional trademark protection.

III. Refining the Examination Standards for the Acquired Distinctiveness of Three-Dimensional Trademarks

1. Factors of consideration in the examination of the distinctiveness of three-dimensional trademarks in China

Similar to ordinary trademarks, three-dimensional trademarks must meet the distinctiveness requirements in order to be eligible for registration. However, for three-dimensional trademarks, especially product shapes or packaging containers, due to consumers’ long-formed cognitive habits of two-dimensional trademarks, the relevant public usually does not spontaneously regard them as signs indicating the source of goods. Therefore, the Trademark Examination Guidelines clearly stipulate that “the three-dimensional shape of the product itself” and “the three-dimensional shape of the product packaging or container” both belong to “signs that the relevant public is not likely to recognize as indicating the source of goods under normal circumstances and are difficult to play the role of distinguishing the source of goods. Generally, they do not have the distinctiveness as trademarks. “Even if ”it has a unique visual effect, it cannot be determined to have the distinctiveness as a trademark solely based on its originality”; only “if it has played the role of distinguishing the source of goods through long-term or extensive use, it can acquire distinctiveness.” Article 9 of the Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Trial of Administrative Cases of Trademark Granting and Confirmation of Rights prescribes similar rules and further clarifies that “the fact that the shape is original or first used by the applicant does not necessarily lead to its having the distinctiveness as a trademark.”

It can be seen that China's current legislative system design essentially denies the inherent distinctiveness of product (packaging container) shapes as trademarks, resulting in almost all such trademarks being rejected in accordance with the provisions of Article 11 of the Trademark Law. Although both the Guidelines and the judicial interpretation do not rule out the possibility of such three-dimensional signs being registered after being recognized as having “achieved distinguishing function through long-term or extensive use,” neither specifies the concrete path to prove “acquired distinctiveness.” The lack of this guidance directly leads to very few cases being able to establish distinctiveness by proving long-term use in the trademark examination practice. In a very small number of cases where the three-dimensional signs are approved for registration during the review of refusal procedure, the following trademarks were determined to have acquired distinctiveness through use:

This case is very similar to the M&G pen case in the examination of the distinctiveness and non-functionality of three-dimensional trademarks, that is, it affirmed the distinctiveness of the three-dimensional sign but determined that the sign has functionality. It is worth noting that the review decision did not specifically demonstrate how the applied-for trademark constituted “the shape that gives the product substantial value”.

2. Consideration Factors in the Examination of the Non-functionality of Three-Dimensional Trademarks in the United States from the Sports Car Three-Dimensional Trademark Case

The author observed that the territorial extension application of the same International Registration in the United States was also rejected by The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), but was finally approved for registration after the applicant submitted a response. Similar to the examination practice in China, the refusal grounds of the US examiner were mainly based on the following two points6: 1. This sign constitutes the “functional design” of the product and does not meet the requirements for registration on the principal register; 2. The applied-for trademark lacks “inherent distinctiveness” and needs to prove through usage evidence that it has acquired distinctiveness. In the non-functionality examination of this case, the examiner explained the basic principles for the examination of the non-functionality of three-dimensional trademarks in the United States in the refusal notice: If a three-dimensional shape is “essential” to the use of the product, or constitutes the purpose of the product itself, or may affect the price and quality of the product, then the three-dimensional trademark has functional characteristics. The examiner also cited the “Morton-Norwich factors” as the exclusion criteria for non-functionality determination:

(1) The existence of a utility patent disclosing the utilitarian advantages of the design sought to be registered.

(2) Advertising materials of the applicant that tout the design’s utilitarian advantages.

(3) The availability to competitors of alternative designs.

(4) Facts indicating that the design results in a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.

If any of the above factors exist, it can be presumed that the sign has functionality and cannot be registered as a trademark.

In this case, the US examiner determined that the three-dimensional sign of the car had functionality based on the retrieved evidence. The logical argument was: The core function of a car is transportation (major premise) → The three-dimensional shape of the applied-for trademark serves the transportation purpose (minor premise) → Therefore, this shape constitutes the essential purpose of the product (conclusion). This argument directly equates the inherent function of the product with its shape characteristics, essentially denying the registrability of three-dimensional trademarks for car-type products and also undermining the value foundation of the three-dimensional trademark system. The author believes this point is debatable.

However, the applicant of this trademark made targeted defenses around the four-factor framework:

(1) Lack of model patent utility or design patent: Applicant has never filed a design patent application, and no design patent has issued, in connection with the Design Mark.

(2) Advertising does not highlight functionality: Applicant’s advertising materials outline the qualities of the engine (the engine is not within the scope of trademark protection).

(3) There are sufficient alternative designs: There are a large number of differentiated designs in the car market, and this shape is not necessary in the industry.

(4) Complex and expensive manufacturing process: The production cost of this design is significantly higher than that of ordinary sports cars, and registration will not force competitors to adopt high-cost processes.

Based on the above arguments, the applicant successfully overcame the refusal.

It can be seen that the non-functionality examination is crucial in the registration of three-dimensional trademarks. The legislative purpose of Article 12 of the Trademark Law is to prevent applicants from monopolizing common product shapes or technical solutions through the registration of functional three-dimensional signs, thereby suppressing market competition and technological development. However, in the examination practice, it is necessary to avoid overly simplifying the determination criteria; otherwise, the legislative value of the three-dimensional trademark system will be weakened. For the non-functionality examination of three-dimensional signs, it can be judged from multiple dimensions, such as whether the sign has practical value, the actual usage methods of the sign by the applicant, the existence of alternative designs, and the impact of the registration of three-dimensional trademarks on competitors in the same industry, so as to avoid overly strictly excluding product shapes from the scope of three-dimensional trademark protection.

III. Refining the Examination Standards for the Acquired Distinctiveness of Three-Dimensional Trademarks

1. Factors of consideration in the examination of the distinctiveness of three-dimensional trademarks in China

Similar to ordinary trademarks, three-dimensional trademarks must meet the distinctiveness requirements in order to be eligible for registration. However, for three-dimensional trademarks, especially product shapes or packaging containers, due to consumers’ long-formed cognitive habits of two-dimensional trademarks, the relevant public usually does not spontaneously regard them as signs indicating the source of goods. Therefore, the Trademark Examination Guidelines clearly stipulate that “the three-dimensional shape of the product itself” and “the three-dimensional shape of the product packaging or container” both belong to “signs that the relevant public is not likely to recognize as indicating the source of goods under normal circumstances and are difficult to play the role of distinguishing the source of goods. Generally, they do not have the distinctiveness as trademarks. “Even if ”it has a unique visual effect, it cannot be determined to have the distinctiveness as a trademark solely based on its originality”; only “if it has played the role of distinguishing the source of goods through long-term or extensive use, it can acquire distinctiveness.” Article 9 of the Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Trial of Administrative Cases of Trademark Granting and Confirmation of Rights prescribes similar rules and further clarifies that “the fact that the shape is original or first used by the applicant does not necessarily lead to its having the distinctiveness as a trademark.”

It can be seen that China's current legislative system design essentially denies the inherent distinctiveness of product (packaging container) shapes as trademarks, resulting in almost all such trademarks being rejected in accordance with the provisions of Article 11 of the Trademark Law. Although both the Guidelines and the judicial interpretation do not rule out the possibility of such three-dimensional signs being registered after being recognized as having “achieved distinguishing function through long-term or extensive use,” neither specifies the concrete path to prove “acquired distinctiveness.” The lack of this guidance directly leads to very few cases being able to establish distinctiveness by proving long-term use in the trademark examination practice. In a very small number of cases where the three-dimensional signs are approved for registration during the review of refusal procedure, the following trademarks were determined to have acquired distinctiveness through use:

In the case involving the three-dimensional trademark of the Head & Shoulders shampoo bottle mentioned above, in the review decision of refusal7, the then Trademark Review and Adjudication Board determined that: “The three-dimensional shape of the bottle involved in the applied-for trademark has been long-term and extensively used as the packaging container of shampoo, hair conditioner, hair-washing agents, and dry shampoo products, and has already had a certain market popularity. The overall shape of the bottle is unique, with a streamlined design on the left side, slightly thinner than the right side, and the bottle cap is in an exclusive blue color with an irregular shape. Combined with the facts ascertained by this Board, the applicant’s ‘Head & Shoulders’ trademark has become a well-known trademark for ‘hair conditioner, hair-washing agents, shampoo’. On the premise that the product has obtained a high market recognition, as an integral part of the product, the relevant public can regard its outer packaging as an identifier to recognize the source of the goods when they come into contact with this three-dimensional sign and establish a unique corresponding connection with the applicant. Therefore, when used on shampoo, hair conditioner, hair-washing agents, and dry shampoo products, the applied-for trademark possessed the distinctiveness required by the Trademark Law and does not constitute the situation stipulated in Item (3), Paragraph 1, Article 11 of the Trademark Law.”

Looking at this review decision, when examining whether a three-dimensional sign has acquired distinctiveness through use, the CNIPA has mainly considered the following two elements: (1) The uniqueness of the overall shape of the bottle (that is, the three-dimensional trademark itself); (2) The popularity of the applicant’s corresponding two-dimensional trademark. However, the proof standard for trademark popularity has a flexible space. What degree of popularity is sufficient to support the acquisition of distinctiveness by a three-dimensional trademark? Does the popularity of a two-dimensional trademark necessarily extend to its three-dimensional sign? Such ambiguities in standard make it difficult for applicants to accurately grasp the specific threshold for proving the acquisition of distinctiveness by three-dimensional trademarks. For example, the three-dimensional sign of another well-known brand “Vidal Sassoon” shampoo under Procter & Gamble was determined in the review decision of refusal8: “When used on the designated goods, it is likely to make consumers recognize it as the common packaging form of the goods, and it is difficult to play the function of distinguishing the source of goods. It lacks the necessary distinctiveness of a trademark”, so it was rejected.

[Trademark No. 50568862]

As an ordinary consumer, the author also has questions: Why do the three-dimensional shapes of the shampoo packaging of the same enterprise, which are both well-known to consumers and whose corresponding two-dimensional trademarks have obtained well-known trademark protection in China, have completely opposite determination results in the review of refusal procedures for their three-dimensional trademarks? Does this indicate that there are other consideration factors in the distinctiveness examination of three-dimensional trademarks?

Fundamentally, the legislative purpose of Article 11 of China Trademark Law, in addition to requiring registered trademarks to have the distinctiveness to identify the source of goods, is also to maintain a fair competition order among operators in the same industry. This principle also runs through the examination practice of three-dimensional trademarks, reflecting the protection of the legitimate rights and interests of competitors in the same industry. If the registration of a certain three-dimensional sign may cause significant harm to the interests of operators in the same industry, it should not be approved for registration. However, due to the one-sided nature of the trademark granting procedure, the use of relevant signs by other operators in the same industry often only appear in procedures such as trademark opposition and invalidation actions submitted by a third party. For example, in the administrative dispute case regarding invalidation of Nestlé’s “square bottle” three-dimensional trademark ((2012) Gao Xing Zhong No. 1750), the second-instance court established an exclusion rule for three-dimensional trademarks to prove acquired distinctiveness through use in the judgment: “In addition to considering the use evidence submitted by the right holder, it is also necessary to examine the actual use of other operators in the relevant market. If no other entity uses the sign in the relevant market, the right holder can, through its own long-term and continuous use, enable the sign to establish a unique and stable corresponding relationship with its goods or services, thereby acquiring the distinguishing function of identifying the source. Conversely, if other entities in the market also use the same or similar signs for a long time and extensively while the right holder is using the signs, and even their use time is earlier or their scope is wider than that of the right holder, the use behavior of the right holder alone is insufficient to determine that the sign has acquired distinctiveness through use.” In this case, since a large number of enterprises in the same industry used similar three-dimensional signs before the filing date of the disputed trademark, the court finally determined that the disputed trademark did not comply with the provisions of Paragraph 2 of Article 11 of the Trademark Law.

Fundamentally, the legislative purpose of Article 11 of China Trademark Law, in addition to requiring registered trademarks to have the distinctiveness to identify the source of goods, is also to maintain a fair competition order among operators in the same industry. This principle also runs through the examination practice of three-dimensional trademarks, reflecting the protection of the legitimate rights and interests of competitors in the same industry. If the registration of a certain three-dimensional sign may cause significant harm to the interests of operators in the same industry, it should not be approved for registration. However, due to the one-sided nature of the trademark granting procedure, the use of relevant signs by other operators in the same industry often only appear in procedures such as trademark opposition and invalidation actions submitted by a third party. For example, in the administrative dispute case regarding invalidation of Nestlé’s “square bottle” three-dimensional trademark ((2012) Gao Xing Zhong No. 1750), the second-instance court established an exclusion rule for three-dimensional trademarks to prove acquired distinctiveness through use in the judgment: “In addition to considering the use evidence submitted by the right holder, it is also necessary to examine the actual use of other operators in the relevant market. If no other entity uses the sign in the relevant market, the right holder can, through its own long-term and continuous use, enable the sign to establish a unique and stable corresponding relationship with its goods or services, thereby acquiring the distinguishing function of identifying the source. Conversely, if other entities in the market also use the same or similar signs for a long time and extensively while the right holder is using the signs, and even their use time is earlier or their scope is wider than that of the right holder, the use behavior of the right holder alone is insufficient to determine that the sign has acquired distinctiveness through use.” In this case, since a large number of enterprises in the same industry used similar three-dimensional signs before the filing date of the disputed trademark, the court finally determined that the disputed trademark did not comply with the provisions of Paragraph 2 of Article 11 of the Trademark Law.

[International Registration No. 640537]

In the administrative litigation of the clover three-dimensional trademark invalidation case, the court also considered the protection of the interests of enterprises in the same industry and upheld the ruling of the CNIPA to declare the disputed trademark invalid. In the second-instance judgment9, the court held that “in this field, a large number of other operators have used ‘clover’ as the decorative appearance of the above-mentioned goods, which further confirms the relevant public’s cognition of the decorative role of the appearance of such products and also weakens the cognition of the disputed trademark in indicating the source of goods... To avoid negative impacts on the legitimate operations of other operators in the formed relevant market, the determination in the original judgment and the accused decision that VAN CLEEF & ARPELS SA’s evidence is insufficient to prove that the disputed trademark has acquired distinctiveness through use is not improper.”

[Trademark No. 15736970]

Based on the above analysis, the current registration examination of three-dimensional trademarks in China mainly focuses on the two aspects of the trademark, which are originality and popularity. In the trademark right confirmation procedure, the competent authority and the court need to analyze the actual use of similar three-dimensional forms in the relevant industry based on the evidence submitted by the parties, so as to balance and protect the legitimate rights and interests of operators in the same industry.

2. Factors of consideration in the examination of the distinctiveness of three-dimensional trademarks in the United States from the Sports Car three-dimensional trademark case

As mentioned above, in the Ferrari car three-dimensional trademark registration application case, the USPTO also rejected its registration on the grounds that the sign lacked distinctiveness. In the Notice of Provisional Full Refusal, the examiner expounded the basic position of US case law on the distinctiveness of three-dimensional trademarks of product shapes: “A product design can never be inherently distinctive as a matter of law; consumers are aware that such designs are intended to render the goods more useful or appealing rather than identify their source. ”Based on this, the examiner determined: “The applied-for trademark is common for car manufacturers to design cars with the same design elements. The attached evidence from Google shows many sports cars feature the same design elements. The proposed mark is not inherently distinctive.” Meanwhile the examiner cited previous cases and listed six factors for determining whether the evidence shows the mark has acquired distinctiveness:

(1) Association of the mark with a particular source by actual purchasers (typically measured by customer surveys linking the name to the source);

(2) Length, degree, and exclusivity of use;

(3) Amount and manner of advertising;

(4) Amount of sales and number of customers;

(5) Intentional copying; and

(6) Unsolicited media coverage.

The examiner particularly pointed out: “Evidence of five years’ use considered alone is generally not sufficient to show acquired distinctiveness for nondistinctive product design marks.” Other evidence needs to be considered comprehensively. And the evidence must relate to the promotion and recognition of the specific “configuration embodied in the applied-for mark” and not to the goods in general. If a three-dimensional sign is determined to be a “functional design”, it cannot be registered regardless of whether it has acquired distinctiveness (constituting an absolute obstacle).

To sum up, the examiner’s examination logic for the distinctiveness of three-dimensional trademarks is: first, deny their inherent distinctiveness, then strictly review the evidence of “acquired distinctiveness” through six factors, and at the same time exclude the registration possibility of functional designs.

In the response, the applicant submitted evidence to prove that: the applicant has continuously used the applied-for trademark for more than 65 years, and the trademark has not been used on a large scale by other entities; reports on the design of the applied-for trademark by authoritative media in the automotive industry prove that the relevant public has associated it with a specific source; the applicant has invested a lot of advertising resources in the design in the US market, and although the relevant advertising materials mention engine performance, through long-term brand binding, the public has associated the design with the Ferrari brand; the Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa sports car, as “one of the most expensive Ferraris ever built”, is positioned at the high end of the market, and its customer groups include famous individuals; the applicant submitted collectable toy model of its design in the market to prove the existence of replica or honor behaviors; at the same time, the applicant submitted spontaneous reports on its design by several automotive industry media, indicating that it can attract public attention without active promotion by the applicant. Through the above arguments, the applicant finally successfully overcame the refusal.

It can be seen that in the US three-dimensional trademark examination practice, for three-dimensional trademarks composed of product configuration, their inherent distinctiveness is also denied in principle, and applicants are required to fully prove that the configuration has acquired distinctiveness through use. However, the US legal practice has established a clearer proof standard through existing cases, and applicants can usually obtain relatively predictable results by submitting evidence in accordance with this standard.

IV. Summary

To sum up, the registration examination of three-dimensional trademarks needs to take into account both non-functionality and distinctiveness being the core elements. In China’s practice, although the non-functionality examination aims to prevent the monopoly of functional designs and ensure fair market competition, its examination standards are not clear enough, and some requirements are ambiguous, resulting in very few cases in which the three-dimensional signs are rejected by applying this provision in practice. The distinctiveness examination strictly denies the inherent distinctiveness of product shape and requires proof of acquired distinctiveness through long-term use. However, there is a lack of clear and practicable guidelines for the specific proof requirements for acquired distinctiveness, making it difficult for applicants to accurately grasp the proof standards. In contrast, the United States has established a clearer path for examination of non-functionality and acquired distinctiveness through case law, providing a more predictable institutional framework for applicants. This structured examination method in the United States is worth learning from, which helps to avoid subjectivity and uncertainty in the examination process. In the future, China should accelerate the construction of its own three-dimensional trademark examination system, formulate clearer examination standards, and ensure the consistency and transparency of the examination. Only in this way can the value of three-dimensional trademarks in encouraging innovation and promoting brand differentiation development be fully exerted on the premise of effectively protecting consumers' rights and interests and maintaining a fair competition order.

——————————————————————————————————————————

1Interpretation of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China

http://www.npc.gov.cn/zgrdw/npc/flsyywd/minshang/2003-09/12/content_321144.htm

2Second Instance Administrative Judgment (2015) Gao Xing (Zhi) Zhong No. 4355

3Second Instance Administrative Judgment (2015) Gao Xing (Zhi) Zhong No. 4355

4“Top Ten Cases of Judicial Protection of Trademark Granting and Confirmation by Beijing Courts in 2022”, Beijing Law Network Affairs, 2023.04.25.

5Shangpingzi [2024] No. 0000079426, 0000079416 “Review Decision on the Refusal of the International Registration 3D Trademark No. 1674041”

6Notice of Provisional Full Refusal and Response regarding the US trademark No. 79345806

7Shangpingzi [2017] No. 0000152948 “Review Decision on the Refusal of the 3D Trademark No. 19119659”

8Shangpingzi [2021] No. 0000364792 “Review Decision on the Refusal of the 3D Trademark No. 50568862”

9Administrative Judgment (2020) Jing Xing Zhong No.4528

2. Factors of consideration in the examination of the distinctiveness of three-dimensional trademarks in the United States from the Sports Car three-dimensional trademark case

As mentioned above, in the Ferrari car three-dimensional trademark registration application case, the USPTO also rejected its registration on the grounds that the sign lacked distinctiveness. In the Notice of Provisional Full Refusal, the examiner expounded the basic position of US case law on the distinctiveness of three-dimensional trademarks of product shapes: “A product design can never be inherently distinctive as a matter of law; consumers are aware that such designs are intended to render the goods more useful or appealing rather than identify their source. ”Based on this, the examiner determined: “The applied-for trademark is common for car manufacturers to design cars with the same design elements. The attached evidence from Google shows many sports cars feature the same design elements. The proposed mark is not inherently distinctive.” Meanwhile the examiner cited previous cases and listed six factors for determining whether the evidence shows the mark has acquired distinctiveness:

(1) Association of the mark with a particular source by actual purchasers (typically measured by customer surveys linking the name to the source);

(2) Length, degree, and exclusivity of use;

(3) Amount and manner of advertising;

(4) Amount of sales and number of customers;

(5) Intentional copying; and

(6) Unsolicited media coverage.

The examiner particularly pointed out: “Evidence of five years’ use considered alone is generally not sufficient to show acquired distinctiveness for nondistinctive product design marks.” Other evidence needs to be considered comprehensively. And the evidence must relate to the promotion and recognition of the specific “configuration embodied in the applied-for mark” and not to the goods in general. If a three-dimensional sign is determined to be a “functional design”, it cannot be registered regardless of whether it has acquired distinctiveness (constituting an absolute obstacle).

To sum up, the examiner’s examination logic for the distinctiveness of three-dimensional trademarks is: first, deny their inherent distinctiveness, then strictly review the evidence of “acquired distinctiveness” through six factors, and at the same time exclude the registration possibility of functional designs.

In the response, the applicant submitted evidence to prove that: the applicant has continuously used the applied-for trademark for more than 65 years, and the trademark has not been used on a large scale by other entities; reports on the design of the applied-for trademark by authoritative media in the automotive industry prove that the relevant public has associated it with a specific source; the applicant has invested a lot of advertising resources in the design in the US market, and although the relevant advertising materials mention engine performance, through long-term brand binding, the public has associated the design with the Ferrari brand; the Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa sports car, as “one of the most expensive Ferraris ever built”, is positioned at the high end of the market, and its customer groups include famous individuals; the applicant submitted collectable toy model of its design in the market to prove the existence of replica or honor behaviors; at the same time, the applicant submitted spontaneous reports on its design by several automotive industry media, indicating that it can attract public attention without active promotion by the applicant. Through the above arguments, the applicant finally successfully overcame the refusal.

It can be seen that in the US three-dimensional trademark examination practice, for three-dimensional trademarks composed of product configuration, their inherent distinctiveness is also denied in principle, and applicants are required to fully prove that the configuration has acquired distinctiveness through use. However, the US legal practice has established a clearer proof standard through existing cases, and applicants can usually obtain relatively predictable results by submitting evidence in accordance with this standard.

IV. Summary

To sum up, the registration examination of three-dimensional trademarks needs to take into account both non-functionality and distinctiveness being the core elements. In China’s practice, although the non-functionality examination aims to prevent the monopoly of functional designs and ensure fair market competition, its examination standards are not clear enough, and some requirements are ambiguous, resulting in very few cases in which the three-dimensional signs are rejected by applying this provision in practice. The distinctiveness examination strictly denies the inherent distinctiveness of product shape and requires proof of acquired distinctiveness through long-term use. However, there is a lack of clear and practicable guidelines for the specific proof requirements for acquired distinctiveness, making it difficult for applicants to accurately grasp the proof standards. In contrast, the United States has established a clearer path for examination of non-functionality and acquired distinctiveness through case law, providing a more predictable institutional framework for applicants. This structured examination method in the United States is worth learning from, which helps to avoid subjectivity and uncertainty in the examination process. In the future, China should accelerate the construction of its own three-dimensional trademark examination system, formulate clearer examination standards, and ensure the consistency and transparency of the examination. Only in this way can the value of three-dimensional trademarks in encouraging innovation and promoting brand differentiation development be fully exerted on the premise of effectively protecting consumers' rights and interests and maintaining a fair competition order.

——————————————————————————————————————————

1Interpretation of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China

http://www.npc.gov.cn/zgrdw/npc/flsyywd/minshang/2003-09/12/content_321144.htm

2Second Instance Administrative Judgment (2015) Gao Xing (Zhi) Zhong No. 4355

3Second Instance Administrative Judgment (2015) Gao Xing (Zhi) Zhong No. 4355

4“Top Ten Cases of Judicial Protection of Trademark Granting and Confirmation by Beijing Courts in 2022”, Beijing Law Network Affairs, 2023.04.25.

5Shangpingzi [2024] No. 0000079426, 0000079416 “Review Decision on the Refusal of the International Registration 3D Trademark No. 1674041”

6Notice of Provisional Full Refusal and Response regarding the US trademark No. 79345806

7Shangpingzi [2017] No. 0000152948 “Review Decision on the Refusal of the 3D Trademark No. 19119659”

8Shangpingzi [2021] No. 0000364792 “Review Decision on the Refusal of the 3D Trademark No. 50568862”

9Administrative Judgment (2020) Jing Xing Zhong No.4528